What Is a Domain Model?

Mike Adams

A plain-language guide to Domain Models

Over the years I’ve noticed something curious: almost every software system has a domain model… yet very few companies ever write it down.

In my last role, I remember two different customers — completely independently — asking whether we had a domain model that explained how API entities related to one another. They weren’t asking for new features or documentation changes. What they were saying, in essence, was: “We’re trying to piece together how these concepts fit, but it isn’t obvious from the API operations alone.”

And the truth is, they had a point. The underlying ideas were there — partly expressed in the database schema, partly in the class structures and behaviours of the code — but not captured anywhere as a pure, conceptual domain model.

That struck a chord with me. I’ve always needed to visualise a system before I can properly understand it; simplifying and modelling things has always been second nature. So when customers struggled, I knew exactly what they were experiencing.

As I’m now making my Universal Hospitality Domain Model (UHDM) project public, this feels like the right moment to answer the foundational question:

What exactly is a Domain Model?

And why is it so useful?

In essence

A Domain Model is simple — far simpler than the name suggests. It is:

A conceptual map of the “things” in a specific area of interest, and the relationships between them.

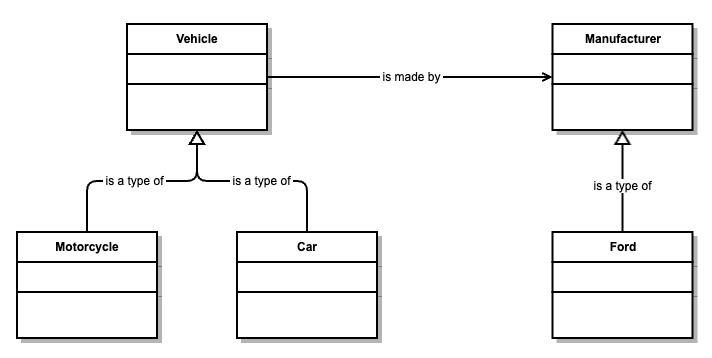

Here’s a straightforward example:

From this, we immediately understand:

- Car and Motorcycle are types of Vehicle.

- A Vehicle is made by a Manufacturer.

- Ford is a type of Manufacturer.

That’s it. That’s a Domain Model.

“Domain” simply means the subject area we’re talking about.

“Entities” are the things that matter within that subject area.

The power of a Domain Model comes from expressing ideas visually, concisely, and in a way that humans can discuss without getting dragged into technical detail.

A picture speaks a thousand words

We could describe the same model in words:

Entities

- Vehicle

- Manufacturer

- Motorcycle

- Car

Relationships

- Motorcycle is a type of Vehicle

- Car is a type of Vehicle

- Vehicle is made by Manufacturer

- Ford is a type of Manufacturer

But the diagram is easier because we understand it at a glance. Our brains think spatially; diagrams help us form a mental picture.

Why domain models matter in software

Software systems are abstract constructions that represent real-world situations. To build anything meaningful, you need to understand two aspects:

- Static structure — the things in the system, and their relationships

- Dynamic behaviour — how those things and relationships change and interact

The Domain Model handles the static structure. Use Cases handles the dynamic behaviour.

A Domain Model is almost always the first step in designing a software system — not because it’s a ritual, but because it’s nearly impossible to build anything coherent without understanding the concepts underneath.

- In a database, tables and relationships often mimic the domain model (even if imperfectly).

- In Object-Oriented Design, objects typically represent real-world concepts, with properties and behaviours that mirror them.

- In APIs, resource models usually reflect entities from the domain (again: imperfectly).

But here’s the key point:

If the domain model isn’t explicit, the system still has one — it’s just hidden inside the code.

And when the model lives only in code, decisions become harder to understand; new developers struggle to join the dots; API users get confused; intent and meaning fade over time.

This is exactly what I saw with customers asking for a diagram: they weren’t confused by the API — they were confused by the implicit domain model behind it.

Value beyond software design

Domain Models aren’t just for engineers. They’re for anyone trying to understand or communicate how a system works.

A good Domain Model:

- Creates shared understanding

- Surfaces assumptions

- Reduces ambiguity

- Helps teams reason about complexity

- Provides a foundation for discussions, planning, and design

Stakeholders don’t need to understand databases, code, or technical jargon. They only need to understand the words and relationships that define the domain.

The Golden Rule: Keep It Simple

A Domain Model loses value the moment it becomes too technical.

Its whole purpose is clarity and shared understanding, so complexity is the enemy.

If someone suggested adding “Horse” as a type of Vehicle, we should be able to debate that immediately. The model should invite conversation, not shut it down.

Yes, software architects and modellers have an advantage — they think in abstractions all day. But a Domain Model should be accessible to anyone with knowledge of the domain, not just the technical team.

So the golden rule is simple:

If it isn’t simple, it isn’t a Domain Model.

What a domain model is not

Domain Models get confused with other diagrams because they often look similar, but they are not the same.

A Domain Model is not:

- A Relational Database Entity-Relation Diagram (ERD)

- An Object-Oriented Class Diagram

- An API Resource Model

These may resemble a domain model, but they represent solutions, not the problem space.

- An ERD describes tables and keys.

- A Class Diagram describes object classes, methods, and structure.

- A Resource Model describes API entities and endpoints.

A Domain Model describes the real-world domain itself — independently of technology. Everything else is an implementation or interpretation of that domain.

In other words:

The Domain Model is the master conceptual view from which other models derive, not the other way around.

What’s an Ontology then?

An ontology is very similar to a Domain Model — so similar, in fact, that the two are often conflated.

An ontology describes the same kinds of things (entities and relationships), but does so in a way that is far more formal and precise. Ontologies usually include strict vocabularies, well-defined inheritance or taxonomy rules, and are often designed so that machines can reason about the information — for example, by using inference rules to deduce new facts.

You could think of an ontology as:

A highly structured, formalised domain model that machines can operate on and interpret unambiguously.

So the difference is largely one of purpose:

- A Domain Model is for humans.

- An Ontology is for machines (and humans).

Both describe the same conceptual landscape — one just does so in a stricter, machine-readable way.

Modelling conventions

When drawing a Domain Model:

- Entities are shown in labelled boxes (“Vehicle”, “Manufacturer”).

- Relationships are shown as lines or arrows with descriptive text (“is made by”).

- “Type of” relationships often use an unfilled arrowhead.

- Optional attributes (like Name, Colour, Capacity) can be listed inside the entity box.

You can add operations or behaviours, but once you do that you’re drifting toward an OOD Class Diagram — and losing some of the simplicity that makes Domain Models useful in the first place.

Closing thoughts: Why this matters

Domain Models give us a shared language. They let us talk about systems without getting lost in technical detail. They help teams — whether technical or non-technical — build a clear mental model of how things fit together.

In industries with complex, fragmented systems (Hospitality included), the absence of explicit domain models leads to confusion, inconsistent terminology, and misaligned expectations. You feel it in APIs, integrations, data analytics, even day-to-day operations.

This is one of the reasons I’m building the Universal Hospitality Domain Model (UHDM): not to invent something new, but to make explicit what is currently scattered, implicit, and often contradictory.

If this article does nothing else, I hope it shows that Domain Models are not mysterious or academic — they’re simply a better way to think and communicate.

And like all good models, they start simple.